Licensing, Joint Ownership and the UPC – What to Watch Out For

February.03.2022

For further insights related to the Unitary Patent and the Unified Patent Court click here.

This article also appeared in the May 2022 edition of leading U.S. professional journal The Licensing Journal.

Not bothering with the upcoming Unitary Patent and Unified Patent Court in your license and other patent-related agreements? Not a good idea, if you want to avoid potentially unpleasant surprises.

This Insight flags key issues in connection with Unitary Patents and the UPC that you should consider in your patent-related agreements already today.

1. License Agreements – Enforcement Rights & Opt-Out

If you are party to a license agreement that allows the licensee to sue for infringement of a European Patent, or are considering entering into one, you should carefully consider the implications of the UPC system, namely the possibility of central enforcement, the risk of central revocation and the possibility of opting out European Patents from the UPC's jurisdiction. This not only applies to new license agreements but to existing ones as well.

While only the patent proprietor can opt out a licensed European Patent, any licensee entitled to enforce the patent can block the opt-out by bringing an action in the UPC before the opt-out is registered. In fact, the parties' preferences regarding an opt-out may not necessarily align. The patentee may be concerned about the risk of central revocation, while the licensee may like the idea of central enforcement, or vice versa.

The issue becomes even more pronounced if the European Patent is licensed to more than one licensee.

Example: Company A owns a European Patent effective in Germany, Italy and the Netherlands and has exclusively licensed it to a different licensee in each country. The German licensee wants to enforce the patent against an infringer in Germany.

In the example above, the German licensee can only enforce the patent in and with effect for Germany. However, unless the patent is opted out, the potential infringer can file a central UPC revocation action and have the patent revoked in all three jurisdictions at once. In other words, there is a mismatch between the scope (and chances) of enforcement on one hand and the scope (and associated risk) of revocation on the other.

There are a few ways to tackle these issues proactively:

As the patentee, you should form an opinion on whether or not to opt out. If you have licensed, or are intending to license, your European Patent to multiple licensees, opting out may be the most practical choice. The safest route to opt-out will be within the three-month sunrise period prior to the start of the UPC. Depending on the relationship with the licensee(s), you may want to consult with them beforehand to agree on a common position. In the case of an opt-out, you should also keep in mind the possibility of an opt-in later on. Ideally, your licensee(s) should have an obligation to inform you prior to bringing any enforcement action in national courts to preserve the option of a timely opt-in.

As a licensee, you will depend on your licensor for any opt-out, opt-in or a refrain from either. If you have a preference one way or the other, you should contact your licensor in time to find a common position and to ensure that any desired opt-out or opt-in requests are duly filed.

2. R&D Collaborations and Co-Ownership – Additional Governance Issues

R&D Collaborations and similar agreements sometimes provide for the joint ownership of any newly created intellectual property, such as patentable inventions. In those cases, the best practice today is to include detailed provisions about the rights and obligations of the respective co-owners with respect to the prosecution of patent applications, the right to use, license, enforce and defend any co-owned patents, as well as the rights and restrictions for transferring co-ownership shares.

One of the reasons for this is that, without any specific agreement, the rights and obligations of the co-owners of a patent or patent application will be governed by the laws of the jurisdiction to which the patent applies. By way of example, if a single invention was protected by four separate national patents in four jurisdictions, there would also be four different co-ownership regimes. And those regimes can be quite different, even across Europe.

Example: Without any agreement to the contrary, under German law, the co-owner of a patent may freely transfer his co-ownership shares to any third party. Under French law, however, the other co-owner(s) would have a pre-emption right. Under Dutch law, without an agreement, each co-owner may individually exploit the patent without having to pay any compensation to the other co-owners(s). Under French law, however, a co-owner exploiting the patent generally will have to compensate the other co-owners who are not exploiting the patent.

The introduction of the Unitary Patent system will add further items to the list of issues that should be considered and addressed in a co-ownership context:

- Approach to Unitary Patent Protection. The parties should agree on the approach to Unitary Patent protection, including whether unitary protection will be sought by default or on a case-by-case basis. If it is case-by-case, there should be a process for reaching an agreement. In this context, the parties should also consider certain strategic options that will be available during the Transitional Period. For example, it may be possible to file divisional applications and request unitary protection only for the divisional, but not for the main application, or vice versa. Accordingly, control over prosecution and agreement on strategic decisions during prosecution will be even more important than before.

- Order of Applicants. The parties should consider the order on how the co-applicants are listed in patent applications. This sounds like a trivial detail, but it can have a big practical impact: it determines what laws are applicable to any resulting Unitary Patent as an item of property, i.e., for issues such as how the Unitary Patent can be transferred, the effects of a license, if and how the Unitary Patent can be encumbered (e.g., with a mortgage or lien) and also the rights and obligations of the co-owners (to the extent not specified in the co-ownership agreement).

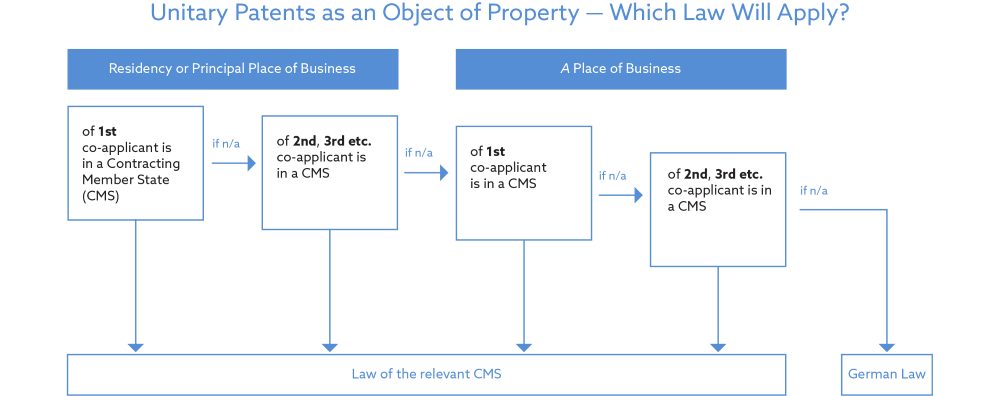

Broadly speaking, the applicable law to Unitary Patents as an object of property depends on the applicant's place of business at the time of the application according to the patent register kept by the European Patent Office. In the case of multiple applicants, they will be considered in the order in which they are listed in the patent register. The following graphic illustrates the concept in detail:

Importantly, the applicable law as determined on the application date will be permanent. It will stay the same even if the applicant later changes its place of business or transfers the Unitary Patent.

- Opt-out / Opt-in of European Patents. With respect to any co-owned European Patents, the parties should define a common position or process for deciding on whether or not to opt out the patent. Importantly, opting out co-owned European Patents from the UPC's jurisdiction will require a joint application by all co-owners. The co-owners will have to instruct and mandate a joint representative to file an opt-out (or opt-in) application on their behalf. Ideally, the co-owners should account for the necessary formalities already in their co-ownership agreement and clearly specify each party's responsibilities.

- Enforcement Rights. Closely connected with the questions around opt-out and opt-in is the issue of enforcement rights. If either co-owner has standing to sue for the infringement of a European Patent, the co-ownership agreement should ensure that enforcement will not conflict with any opt-out or subsequent opt-in intended by the other co-owner(s) through suitable requirements for prior consultation or even consent.

Each of the above issues may be more or less critical depending on the specific circumstances. The key point is to be aware of them in order to make an informed decision.